Dreams that Money can Buy is an ongoing text work consisting of (currently 31) dreams that I have written down over the last 8 years after waking up. The connection between these dreams is that they all tell of encounters with other artists and their dreamed (fictional) works. This “dreamed group show” not only offers an unusual view of artworks and art production, but also raises questions about authorship: Who is the author of a dreamed fictional work? Me, the dreaming body or the original artist whose way of working has solidified in my subconscious - or perhaps the dreaming “I” is even an independent entity, an author and creator in its own right. Read more about the work with a text by Julia Moebus-Puck.

Exhibition view, Sperling Munich, 2022

(1) I‘m riding my bike in a city in the evening. Suddenly I am stopped by a policeman. He inspects my bike and notices that there is only one reflector instead of the required two. The policeman says that I will get a fine for this. I reply whether he could not make an exception, since my bike is otherwise in perfect condition. The policeman denies, because he has to keep to the rules. Then we are interrupted by loud squeaking and clattering noises. An old man arrives on a bicycle, which looks like a moving pile of metal. Chairs, buckets and other metal parts are randomly welded together and hang down to the ground. I threatens to fall apart at any moment. However, the policeman kindly lets the man pass. I ask irritably why he doesn‘t stop the man, since he doesn‘t even have a light. The policeman answers that this was the artist Daniel Spoerri and that he is allowed to drive around like this.

(16) I am standing in front of a dilapidated or destroyed bridge pier. Rubble and construction debris are piled up everywhere. It turns out I’m in Beirut, and what you see is the damage from the silo explosion. Next to the bridge pier is a small gallery where the artist Charbel-joseph H. Boutros exhibits. The gallery’s door and window are barricaded with wood, and you can’t go in or see inside. Instead, the artist has installed his works directly on the bridge pier. There, spread out, hang numerous white posters, each with a large black word written in French: “Soluable”, “Crystalline” “Transparent”, “Solid”. I ask the artist what these words mean, and he explains that they are the properties of salt. Then he tells me that the explosion in Beirut was caused by salt. Traces of this salt are now everywhere in the city and even in the people. He says that the properties of salt will slowly transfer to the properties of the people from now on. I nod in understanding.

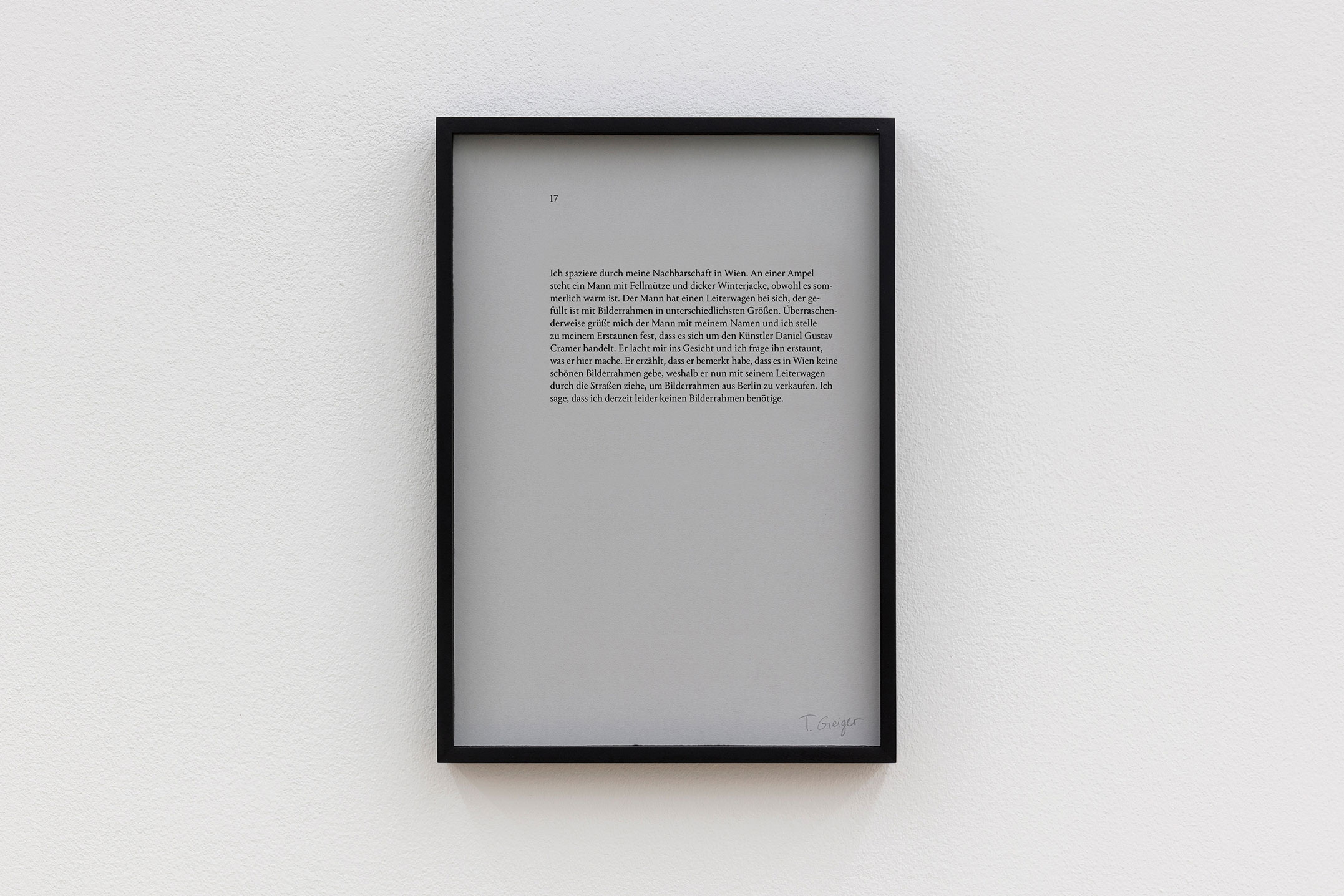

(17) I walk through my neighbourhood in Vienna. At a traffic light stands a man wearing a fur hat and a winter jacket, although it is summery warm. The man is pulling a cart with him, which is filled with picture frames of various sizes. Surprisingly, the man greets me with my name, and I realize to my astonishment that it is the artist Daniel Gustav Cramer. He laughs in my face, and I ask him in amazement what he is doing here. He tells me that he noticed that there were no beautiful frames in Vienna, which is why he now roams the streets with his cart to sell frames from Berlin. I say that, unfortunately, I don‘t need any picture frames right now.

Exhibition view, Sperling Munich, 2022

(21) I am in a small bookstore in Paris. The shelves are filled to the ceiling with books. There are also piles of books on the bright wooden floor. Despite this abundance, the room has a tidy, orderly atmosphere. I browse through the shelves and notice that the store seems to have a lot of atlases. Everywhere I look, I see atlases: large, small, colourful, black, and white, brand new, and antique. Suddenly, I hear a voice behind me. I turn around and the bookdealer asks me if he could help me. To my astonishment, I discover that it is the artist Jonathan Monk. I ask him what this collection of atlases is about, and he tells me that this is a newwork of his. I turn back to the books and in the background, I hear Jonathan Monk talking at length about his work. I hear that he has removed something from all the atlases. However, he does not want to reveal what it is, and so I start to search intensively, but without finding anything.

(25) I visit an art fair together with the artist Josef Zekoff. We stroll between the gallery booths and look at the numerous works. Suddenly Josef suggests stealing a work of art. I look at him in disbelief, but am quickly motivated by the euphoric expression on his face. We look for an unattended stand and walk inconspicuously between the works. I immediately spot a work by Francis Alÿs and say to Josef that I‘ve always wanted it. It‘s a square picture frame measuring about 30 x 30 cm. The frame is colorful and densely painted. The yellow, green, red and blue areas, lines and dots are reminiscent of finger paintings that could have been made by a child. The frame captivates me so much that I pay no attention to the actual work inside. I quickly put the work in my backpack and turn to Josef, who is leafing through some drawings on a table. Josef puts some drawings in his pocket and we decide to leave. On the way out, I am overcome by a guilty conscience.

(26) I am walking next to the artist Heinrich Dunst on a sidewalk in Vienna. Meanwhile, I tell him about my work “I want to become a millionaire” and the so-called Artists Sheets. These are special editions of my Millionaire Sheets, in which other artists place their own work on my sheets. I ask Heinrich Dunst if he would also like to make Artists Sheets for me and, to my delight, he says yes. I immediately give him some sheets of paper, which I take out of my jacket pocket. Heinrich Dunst looks at the sheets and smiles. Then he says that he will hide his finished editions in Vienna at Easter and that I will have to look for them.

Exhibition view, Sperling Munich, 2022

(27) I am in a kind of sports – or exhibition hall in which a dense and multi-part exhibition is installed. I see large, colorful text banners, video screens, showcases, paintings. Everything is colorful and here and there something flashes and lights up, and it feels a bit like at a fun fair. I read on a wall text that the exhibition was curated by WHW and brings together political artists from Eastern Europe. Then I am drawn to a group of people, all dressed in blue workers‘ suits and holding protest signs. Unfortunately, I can‘t read the messages on the pictures, but I learn that they are a group of Greek artists whose work is directed against the war in Ukraine. Suddenly the blue men and blue women line up in three rows and start singing “Bella Ciao” at the top of their voices. The exhibition space darkens and the lights start to flash, like in a disco.

(28) I meet the artist Stephanie Saadé on the street. She tells me that she is currently working on an artist‘s book and that I would definitely like her project. Curious, I ask what kind of book it is. She tells me with great pleasure that she is not going to print her book on paper, but will have all the pages tattooed on her body and thus become a book herself. Impressed, I ask if she will also have the ISBN number tattooed on her body? She nods and says: »Of course!«

(30) The artist Johannes Wald stops next to me on the road on a touring bike. Johannes looks like he‘s on a long tour because he‘s packed with panniers and wearing professional cycling gear. I notice a small detail on his bike: above the front wheel there is another small pannier rack, on which a small marble block is stretched in an eye-catching construction of metal straps. I get closer and see that the marble block is in the shape of a book, with a cover and finely crafted edges. The cover reads “Johannes Wald: Journey”. I ask Johannes what it‘s all about and he tells me that he is going on a bicycle tour through Europe. His journey, his experiences, the weather, all of this is invisibly inscribed in the marble book. He says that the marble will become a documentation of the journey.